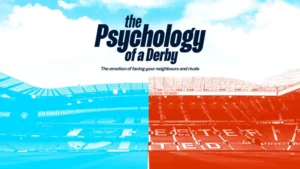

Local derbies are the lifeblood of football.

Men’s Team

How can I watch the 2024 FA Cup final on TV?

For fans all over the world, there is little sweeter than getting one over your neighbours.

Derbies can also be about so much more than just what happens on the pitch.

Fans co-exist in daily life throughout the year, with bragging rights often only earned on two occasions across a 10-month season.

Brazil and Argentina

When most football fans think of derbies, their mind instantly takes them to South America.

It could be Buenos Aires and the iconic shots of La Bombonera or El Monumental, with toilet roll streaming down the stands, as the blue and yellow of Boca Juniors comes up against the red and white of River Plate.

In Rio de Janeiro, Flamengo and Fluminense is just as colourful and chaotic, with beautiful, brutal football a staple in Brazil.

Advertisement

a writer who specialises in South American football, articulates, these games are often mean so much to more people than just the local population split down the middle.

“Derbies are not only for bragging rights at school, work or over the dinner table, but often about how we see ourselves,” he starts.

“They strike at the heart of our identities, likely more so in South America than England. Football played a major role across continent as postcolonial populations sought to discover their sense of self and define their national identities.

“Moreover, much of South America has centralised footballing makeup, with clubs clustered heavily in major cities, often leaving supporters with the option of aligning themselves to the clubs that best represents them.

“And so many clubs were founded based on nationality, religion, social class. Your club is more than just who you support, it’s who you are, and the continent’s obsession with the game means everyone has to have one.

“As Eduardo Galeano put it, football is the ‘the only religion without atheists.’”

2024 FA Cup final | Match preview

Speaking about the ‘Superclasico’ of Boca v River specifically, outlines how the identities of the two clubs shaped that rivalry in the early years.

“Both teams began life in the working class area of La Boca before heading in different directions,” he says.

“A common misconception is that River Plate are referred to as ‘the Millionaires’ because they left La Boca for the snooty suburbs of Nunez. However, they in fact earned that nickname due to the club’s early outlay on large transfer fees.

“Regardless, that move certainly brought about an initial class divide and shaped the identities of the two clubs: River became known for their expansive, enchanting football – winning well, rather than just winning – while Boca were built on blood, guts and desire as a ‘team of the people’.

“That has now long been transcended, however, as both have significant support from a wide range of social demographics.”

It’s a similar story over in Rio, where two names recognised all over the world battle it out.

Fla-Flu is one of football’s great historic rivalries, with the rivalry traced back to the very beginnings of organised sports clubs in Brazil,” says Fryer.

“Flamengo was initially founded as a rowing club whose football division was actually founded by a group of disgruntled Fluminense members who defected to their cross-town neighbours.

“Much like the Superclasico, there is an historical class divide – Fluminense, founded by British aristocrats, was seen as ‘the club of the elite’, while Flamengo, the best supported team in the country, was the ‘team of the people’.

“While that, too, has totally transcended the class divide in modern Brazil, it still carries significance, with even the country’s political split being ‘dubbed the Fla-Flu divide’.”

The 2018 Copa Libertadores final remains perhaps the most globally renowned iteration of the Superclasico, with River and Boca playing off for the continent’s biggest club prize over two legs.

The first leg finished 2-2 at Boca’s home but safety concerns saw the second match taken out of Buenos Aires and moved to Madrid instead.

“For the general population, the build-up to this tie brought two weeks of complete hysteria and culminated in the inevitable: An event so big that the country simply couldn’t handle it – and so we ended in Madrid.

“River fans, of course, still lord the victory over their rivals. Boca fans respond by suggesting that title should come with an asterisk after the Boca team bus was attacked and the final moved to the other side of the world.”

+ There are no comments

Add yours